Monday, 21 December 2009

popularity

Thursday, 17 December 2009

some highlight of today’s poster session

Some of the posters which particularly caught my eye today include:

Poster #V43E-2322: A new garnet, {(Y, REE)(Ca, Fe2+)2}[(Mg,Fe2+)(Fe3+,Al)](Si3)O12, and its role in the yttrium and rare-earth element budget in a granulite, by E.S. Grew; J.H. Marsh; M.G. Yates; A. Locock. They’ve named this particular type of garnet, which is very rich in yttrium (up to 17%), after Georg Menzer (1897-1989), who was a German crystallographer who first solved the structure of garnet.

Poster # V43D-2297. Subduction/exhumation of UHP rocks in Silurian-Devonian continental collision, northern WGR, Norway, by P. Robinson & M.P. Terry. They’ve got some wonderful photos of some spectacular outcrop in Norway which reinforces my desire to move to Scandinavia one day.

Another poster is a bit different—it is a Monday poster, but he’s brought it back every day, finding a bit of blank wall to display it each day. When I saw it just a bit ago it was in the Volcanology section at poster slot #2305, but if that spots turns out to be needed by someone else he will move to another open spot. He is collecting signatures on a petition to have a park boundary in New Jersey extended by 200 feet, to protect a lovely outcrop in a quarry wall. Apparently the old quarry is slated to become the site of condominiums, and if that happens the outcrop will be lost. He has lovely photos of some of the significant features of the outcrop, including dinosaur tracks and a variety of volcanic features. His goal is to collect 1000 signatures, so if you are at the conference, please stop by his poster, have a look, and if you think the outcrop worth preserving, sign his paper. Having seen the outcrop that Hutton had preserved from the quarry workers in what is now Hollyrood Park in Edinburgh, Scotland, this summer, I can attest that it is neat to visit a significant outcrop a couple of hundred years after someone had intended to destroy it, but another rescued it.

Stop by my poster session this afternoon

Life is wonderful

It was very interesting to hear what each of us bloggers had to say by way of introduction, and amusing to note that we were all long winded enough that the lunch went longer than scheduled.

Wednesday, 16 December 2009

The highlight of the AGU meeting (so far)

The combination of these comments prompted me to wonder what arrangements they’ve made for the continuation of their work when they are no longer able to continue. Are they training their students to continue to expand the data set? Is there someone out there who is able to continue to refine the coding of the programs as new information is available that suggests potential improvements? Since I didn’t actually get to meet either individual, I didn’t have an opportunity to ask, nor, do I think, would it be the most appropriate of questions. I do know that they’ve delegated the maintenance of the Thermocalc web page therefore it wouldn’t surprise me if they have other collaborators working with them to keep their tools growing and accessible into the future, even if they decide to retire at some point.

how nice it is to enjoy a morning with no crises needing to be solved

I am very much looking forward to the geoblogger’s lunch today, and have arranged to meet a friend who works in the city for desert afterwards (good thing my plan for the day is posters only!)

Today’s tribulations brought to you by my own carelessness

As a result of this history, I resolved to print my poster for AGU here in the US, rather than bringing it with me from Europe, as I knew there would be any number of opportunities between departing and arriving at my final destination to misplace an important item. This decision came with two additional advantages 1) more time to complete the poster and 2) not needing to worry about the recent tendency of the airlines to severely restrict how much carry-on baggage their clients may bring with them. However, this plan, as so many do, encountered a minor change. While my poster is still being printed on this continent, one of my colleagues called me on the Wednesday before I left asking if I would be willing to carry a poster to the meeting for them, since I was not flying until Friday, and the others on my research team were leaving on Thursday. I agreed, and the poster was delivered to my office on Thursday evening.

I successfully carried the poster with me to California, managing to keep my hands on it through customs and the change of plane in New York, and when disembarking in San Francisco. I kept it with me for the trip to the Santa Cruz Mountains, where I stayed with friends, and kept it with me for the trip to Berkeley for a Medieval Event. I even kept it with me when transferring to another car in Berkeley for the journey to San Rafael, where I transferred to yet another car before heading on to Petaluma on Saturday evening, though I managed to leave my pillows in the car in Berkeley. Unfortunately, after adventuring on Point Reyes on Sunday with friends I failed to put the poster back into the car before heading to Oakland for a Hanukah party (Judaism optional, our host said) at another friend’s house. We didn’t realize the mistake until they dropped me off in San Francisco on Sunday evening. I told my friends that the poster in the tube needed to be on display on Tuesday, and they assured me that they would bring it to the city on Monday.

Relieved that the problem would be solved in plenty of time, I wished them a good night and sent them on their way. However, on Monday I received a Facebook message from my friend letting me know that it was cheaper to send the poster tube to me via FedEx than to drive back down to the city again, so they did, and it should be delivered the next day. I thanked her, and didn’t really think about the timing issues, until later that evening, when I looked at my schedule, and realized that the next day was Tuesday, which is when the poster needed to be on display. Unfortunately my friend was no longer on line, I didn’t have a phone number for her, and she hadn’t given me a tracking number for the shipment.

I went to sleep Monday night hoping that FedEx would do the delivery first thing in the morning. They didn’t. I checked Facebook to see if she had replied to my request for a tracking number. She hadn’t. I tried calling another friend, for whom I did have a phone number, to see if I could get the number of the friend who had done the shipment, but he wasn’t answering. I consulted my schedule, and realized that there were two talks on Tuesday morning that I really, really shouldn’t miss (post on them later, I hope), starting at 10:20. Since it is an hour walk to the conference venue from where I am staying, I decided to leave at 9:00, and then return after the two talks (which meant canceling a lunch meeting with another friend). Accordingly, after the talks (which I enjoyed), I took a cab back to the house, in hopes that it had been delivered and I could rush it straight back to the conference. No poster tube. I checked Facebook. No reply. I called the friend whose number I had, he answered and gave me the phone number for the friend who had done the shipping. I called her. She couldn’t find a tracking number on her receipt, but she could find some other numbers, and she had a number for FedEx. Called FedEx. They managed to find the shipment without the tracking number, and told me that it was in Sacramento and hadn’t been sent to San Francisco yet. He also said that the sender could change the delivery address, but I couldn’t. I called her back and asked her to call them to arrange delivery directly to the conference, which she did. It still hadn’t been delivered in the time it took to return to the conference and type up the following, which I posted on the poster board. It is a sorry substitute for the poster they worked so hard on, but it is better than a blank wall, I think:

*******************

A Public Apology

Poster # V23C-2074, The basal fallout and surge deposits of the mafic ignimbrite-forming Villa Senni Eruption Unit, (Colli Albani volcano, Italy), was hand-carried safely from Italy to California on behalf of its authors. However, do to carelessness on my part, was inadvertently left behind in Petaluma on Sunday. The problem was discovered as I was dropped off in San Francisco that evening, and my hosts agreed to bring the poster tube in to the city during the day on Monday.

Unfortunately, it turns out that I failed to communicate the urgency of the need to have the poster delivered on Monday, and they chose to send it via FedEx that morning, rather than doing the drive back to the city themselves. As of 14:00 Tuesday, the day the poster is meant to be on display, FedEx has still not delivered the package.

I hereby apologize for the inconvenience to everyone who was interested in viewing this poster, and assure you that if the delivery is made before 18:30 I will put the poster up promptly. Unfortunately, FedEx gives their drivers the option to deliver at any time between 08:30 and 20:30, so it is possible that it will not arrive before it is time to remove it. The fault is entirely mine.

*********************************

I signed the apology with my full legal name, but not the name of my University, as they don’t need their name associated with my failure to get the poster where it needed to be in a timely manner. I also printed a copy of the abstract and posted it, as well. If you would like to see this abstract, go to the AGU session planner and search for the poster number.

Tuesday, 15 December 2009

some preliminary AGU impressions

(written Monday evening, posted Tuesday afternoon; which was the next chance I had to be line long enough to post)

Attending such a large conference (plus or minus yesterday morning’s trials and tribulations) caused me to revert to my childhood habits of not actually interacting with anyone other than those individuals in official positions with whom I needed to interact to achieve the goal of the day (actually being permitted to attend the conference). Once I had my registration in hand I took my computer to one of the handy tables with power points provided (certainly an advantage of a large conference!) and settled in to first check e-mail to see if anything important had come in (I managed to avoid the temptation to lose hours reading non-urgent e-mail and blogs) before finishing up my poster.

By the time I had it complete and e-mailed off to be printed it was well into the afternoon, and I, finally, consulted my schedule for the day. I lead something of a charmed life, in that the schedule of interesting sounding talks and posters I’d prepared before the meeting started contained nothing but poster sessions in the morning and early afternoon, and a couple of talks in the late afternoon. Therefore I packed up the computer and wandered over to the poster session room and spent some time learning the logic of their organizational system. It turns out that the letters in the names of the session are abbreviations for the full session titles, and there are large signs hanging above the posters, in a font so large that they can be read at great distances, directing people to posters relating to Volcanology, Geochmistery and Petrology (V), Tectonophysics (T), Education and Human Resources (ED) or whatever. In addition there are even larger numbers hanging above the posters, so that if you are looking for V13D-2056 the fastest way to find it is to look for the huge sign reading “2000” and head to that region of the (very, very large) room, and then start looking at the smaller signs at the end of each row.

After finding a few interesting posters (but not actually speaking with their authors) I returned to the other building, where the lectures were being held. Consulting the schedule and map revealed that the two talks I’d put on my schedule were scheduled to take place one right after the other, but in rooms on the opposite side of the building. The one scheduled for 17:15 is by a colleague of mine, so I opted to just go to the room in which he would be presenting, to be certain that I wouldn’t miss his talk. The talk which preceded it, while it hadn’t come up in my pre-meeting keyword search of the schedule as something I would wish to seek out, turned out to also be interesting, and it was nice to just sit still for a bit and listen to lectures while making some progress on the sewing project I’d brought with me. After my colleague’s talk I chose to slip out a bit early, because I was somewhat tired and worn out for the day, and went back to the home of my friends where I am staying this week, where I enjoyed some quiet conversation (and more sewing) before doing my daily yoga and going to sleep early for the first time this trip.

Monday, 14 December 2009

The trials and tribulations of attending huge conference

As I reached the conference center there was no mistaking I’d arrived, since there is a row of AGU banners outside. I went into the building, and the first thing I saw was three booths set up just inside of the entrance, one whose sign indicated that one could pick up one’s posters there, one whose sign I’ve forgotten, and one labeled “exhibitor’s registration”. There was a short line for that one, so even though I wasn’t certain if it was what I wanted (does exhibiting a poster at the poster session make one an “exhibitor”?), I stood in it nonetheless. Once I got up there I found out that my hesitation was well founded, “exhibitor” refers to businesses with booths, and I needed to go to the other building, across the street, for registration. Off I went, and soon entered a huge hall, with booths along the wall facing the door labeled “on site registration” and booths to the side labeled “pre-registration”. Guessing that “pre-registration” actually meant “people who have pre-registered”, I found the line for the correct section of the alphabet, and stood in it. Many minutes later it was my turn, but after much searching through her stack of cards she was unable to find my paperwork.

So then I went and stood in the “registration help” line. Many minutes later it was finally my turn and I explained that they couldn’t find my name. She looked in the computer and couldn’t find me there either. I explained that I remembered registering, that I was presenting a poster, and was a recipient of a student travel grant. She let me know that many students were having the same problem—that when we did the abstract submission we should also have gone to a separate part of the web page to register for the conference itself, but there was nothing on the web page prompting us to do so. However, I had memories of filling in forms on the web indicating that I wouldn’t be doing the conference dinner, that I am a vegetarian with an allergy to wine/vinegar, and so on. Assuming that this memory is both correct, and attached to this conference and not some other conference, I should be registered. So I briefly turned on my computer and checked my records, but of the e-mails I’d received from AGU I could find only the abstract submission and acceptance, and I quickly turned it off again, before the battery went flat. Sigh. I’d *thought* I’d registered, and certainly the web page at the time I did the abstract submission led me to believe I’d done all of the necessary paperwork to attend the conference. So, how to pay for it now? I couldn’t remember if I had sufficient cash in my Alaskan bank account to cover the cost of registering, and my “visa” card there is only a debit card, so I didn’t wish to risk using it. My European “master card” is a pre-pay card, and, again, I couldn’t remember how much cash remained on the card (I keep all of these records on my computer, not in my brain, but I didn’t wish to tax my inadequate computer battery by turning the computer on again without plugging it in). In addition I don’t really care to pay the fees associated with using a European card in the US. Therefore logic says to pick up the travel grant check, cash it, and use that cash to pay the registration fee. The lady at the registration desk didn’t know where the travel grant checks were located, but thought that it might be at the education booth just over there. Off I went to that booth, where there was no line at all (yay!). The nice lady there was sympathetic to my plight, and thought that the checks would be in the other building. However, without a badge showing I’d paid, she didn’t think I would be able to get into the room. So she called the person in charge of educational related stuff, who said that she’d come to me, and soon thereafter I had my travel grant check in hand. I found out where to find the bank upon which the check was written, and walked the few short block there, where, again, there was no line. The nice young man there cashed my check, and then told me that since I don’t have an account with them there would be a five dollar fee. Oddly enough, that announcement was enough to push me over the line in terms of stress levels, and I promptly burst into tears, which made the poor boy feel very bad for charging the fee. If I had been able to stick with plan A (take check with me to Alaska and deposit it into my account there), I would not have been charged the fee. However, not wanting to use my “credit” card, cash was my only option, so I let him charge me.

Back to the conference center I registered. While I asked nicely, they were not willing to let me register with the fee that would have applied on the day I did the abstract payment, even though I would have happily registered on that day, had there been any indication that I needed to do so separately. This entire process took over two full hours, but I am now properly registered, have my badge, and am free to attend lectures and poster sessions. However, I still need to put the finishing touches on my poster and print it, so it could be a while before I have any science to report from my conference attendance experience.

Thursday, 10 December 2009

schedule printed

Wednesday, 9 December 2009

preparations for AGU winding to a close

So, what factors conspire to make it take longer than I would like? There are several; learning to use Mathmatica, which program, while very powerful, is also very fussy about the format of the data one presents it, having had time to run only three experiments thus far, and, as I’ve mentioned in prior posts, having some of them run water-undersaturated, resulting in very small grain sizes, making it difficult to obtain good analyses with the microprobe, and taking a couple of days off last week to fly to Stockholm for a symposium on Medieval music and dancing in the way of a pre-birthday celebration. (Note: when I purchased the tickets for that adventure I didn’t know yet if I’d be able to attend AGU or not.) Now that I’ve (finally) got my data into the correct format and graphs have been produced I am feeling much better about my prospects of completing everything on time. However, I am highly amused at the fact that I’d long since decided to print my poster after I reach California, in part so that I wouldn’t have to carry a poster-tube with me in these days of severe luggage restrictions, and just now I received a phone call from a colleague who asks if I would be willing to transport his poster to the meeting for him. So much for that reason to delay. However, I still have another fine reason: so that I can speak with the printer in English about what I want done, rather than trying to use the local language to place the order. (Never mind that I successfully printed a poster for the conference in Edinburgh back in July even though the clerk at the print shop spoke no English whatsoever.)

Thursday, 3 December 2009

the transition zone has its advantages

Today I found out that the way the AGU funding works is that we pick up a check when we arrive at the conference, and we have until the 15th of January to turn in all of our receipts for the expenses. Apparently if our total expenses are less than our accumulated expenses we need to then give back to AGU any funds we didn’t need. If I had opted to stay in a hotel during the conference my total expenses would easily exceed the total amount of the available funding. However, a very good friend of mine happens to live in the city, fairly near the conference venue. Therefore, instead of staying in a hotel, I’ll be staying with friends. Because I managed to find a very good deal on my air fare (as one does when one has to front the money oneself and one’s budget is tight just now) I strongly suspect that I won’t actually accumulate enough additional receipts to use up all of the funding available to me. (They won’t fund more than $45/day for food, so don’t suggest going to really high end restaurants to use it up.) Therefore, so that I don’t feel like giving their money back is an expense, my plan is to record both the influx of the advance, and, on the same day, enter in the outgo of the change I owe them. Initially, I’ll record the value of that “change” as the difference between the total funding available and the cost of the air fare. Then, each time I spend money on food or public transit during the conference, I’ll change the number in the “unused funding” entry. I don’t expect that I’ll manage to reduce that number all the way to zero, but it will be interesting watching it change as the expenses accumulate.

Friday, 27 November 2009

routine + templates makes things easier

The first time I did this it felt difficult to compare those numbers with the actual, known, bulk composition of the samples, since this rough-area scan is never going to give precisely the same numbers as the bulk composition. The growth of minerals within the powder has caused some elements to be concentrated in some minerals, and other elements in other minerals. However, in general, the relative differences between the two bulk compositions can still be distinguished via the rough scan. Therefore I set up a spreadsheet with graphs, plotting the original, known, bulk composition in one colour (hollow symbols for NM and solid symbols for NP), and the rough area scans of the first experiment in another. Sure enough just as the original bulk NM is higher in Al2O3 and lower in K2O FeO and CaO than is NP, so the first experiment has one capsule with higher Al2O3 and lower FeO, K2O, and CaO than the other. The second experiment repeated the pattern, but now that I’ve added the third the graph is even easier to read, for now the symbols for the NP bulk plot in one distinct clump on each graph, whilst the ones for the NM bulk composition samples plot in another. This means that from here on out, I need only enter in the new data into the spreadsheet, and in a second’s glance at the chart I’ll know which is which.

Somehow, I really enjoy these tricks which make life easier. Besides, it is fun to set up the charts and graphs.

Two weeks left to finish analyzing the data from my first three experiments and prepare my poster for AGU. Somehow, I suspect that this will keep me as quiet on the blog front as the past couple of weeks when I had both unpacking to do and thesis corrections to make (since my household goods and the examiner’s report arrived on the same day).

Tuesday, 17 November 2009

blogging at AGU

Sunday, 15 November 2009

Experimental petrology defined

However, knowing that the vast majority of the people out there haven’t a clue what that means, I wrote him the following translation:

I am a Geologist who inflicts extreme heat and pressure on tiny amounts of powder (of known composition, which is similar to a specific rock type) for one to three weeks at a time. I then analyze the minerals which grew from the powder to determine which ones are present, and the precise composition of each. Once these experiments have been repeated for a variety of temperatures and pressures (each of which is comparable to specific depths under ground) it is possible to determine which chemical reactions are happening at which temperatures/pressures (for that specific composition). This information is then used (both by myself and by other geologists) to help calculate the temperatures and pressures at which real minerals in real rocks probably grew.

Tuesday, 10 November 2009

note to self

Photos of thin sections are taken in either crossed-polarized or plane-polarized light. Just because plane polarized light photos tend to be less colourful than crossed-polarized light photos does not make them “plain”.

That’s it. You may now resume your other blog reading. Hope my lesson brought a smile to your face.

Making choices

There was one statement in the examiner’s report which raised my eyebrows a bit. One of the two examiners expressed “surprise” that I made no use of Thermocalc “pseudosections”, which said examiner has found to give consistent results for a variety of compositions. He is correct; my thesis did not make use of that particular program for that task. Instead I used the program Perple_X, to which I was introduced first. I did consider also learning Thermocalc, and Theriak-Domino as well, since each program approaches the task slightly differently. However, it was recommended to me that rather than learning several different programs for the same sort of tasks that I instead focus on one and use the time not spent learning the mechanics of the other programs generating additional data for other aspects of the thesis. Around this same time I read a paper* by an author who did take the time to use those three different programs to model the same samples, and achieved similar, though not identical, results with each. The advice sounding reasonable to me, and the paper further convinced me that since different tools will give similar results that the important thing was to simply choose one of them. I can fully understand having a preference for one program over the other when doing such modeling and creating such diagrams, but never will I be surprised if a student working on their PhD chooses to go with only one program to accomplish a specific type of task. Today’s students are given a limited amount of time to complete their degree and failure to submit the thesis by the University imposed deadline results in loss of funding/support. Given such constraints it is not possible to use every program available, without sacrificing other sections of the research and some choices must be made.

*Hoschek, G., 2004. Comparison of calculated P-T pseudosections for a kyanite eclogite from the Tauern Window, Eastern Alps, Austria. European Journal of Mineralogy, 16(1), 59-72.

Tuesday, 3 November 2009

first experiment photos

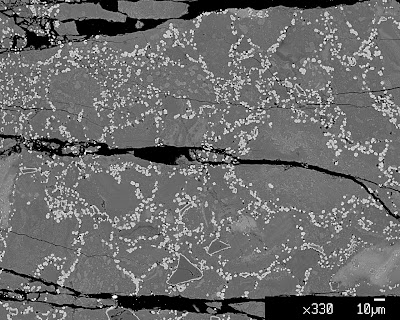

These are back-scatter electron images, which means that the brighter the pixel, the heavier elements present at that point (and the darker the pixel, the lighter the element). The bright ring-like objects are rims of iron-rich garnet growing on the seeds of Mg-garnet that was present in the powder before running the experiment. The bright dots of the same tone of brightness as the rings are new Fe-rich garnets growing in the matrix. As you can see, there is a pronounced difference in quantity and size between the two samples. Note the difference in the scale bars between the two photos.

Monday, 2 November 2009

water is important for growth, even for minerals

As a result of my welding trials and tribulations I’ve had mixed success in the “sealing” part of the above paragraph. Despite the issues with my first attempts at sealing, we ran my first experiment nonetheless, giving two samples a week and a half at elevated pressure/temperature (in this case 650 C and 25 kbars). Once they were “cooked” we had the gold capsules mounted into small disks of epoxy, then carefully polished the disks until the insides of the capsules were exposed. During the polishing stage we received our first confirmation that they had not achieved the same level of “sealed”. Apparently when properly sealed the presence of water inside the capsules ensures that the pore space in between the grains of powder are occupied, and as a result even the high pressures to which we subject them aren’t enough for the new minerals to properly interlock when they grow. As a result, while there are new crystals present, the texture isn’t very rock-like, and when polishing it is easy to accidentally remove clumps of the sample itself. This is the texture we were anticipating, and, for one of the samples run in the first experiment, this is exactly what happened. In these cases we polish only enough to just expose the inside of the capsule, then add more epoxy, letting it soak down into those pore spaces and let it dry before completing the polishing process without so much risk in losing what we are trying to polish.

However, in the other of the two samples run in the first experiment I must not have done the final welding properly, because the contents of the capsule were much harder, and held together better, meaning that the pore space was not held open with fluid when the minerals were growing. This was obvious during the polishing process, so I was able to go quite a bit deeper into the capsule (remember these are only 2 mm in diameter and about 5 mm long so “deeper” is only a relative term) before needing to add the additional epoxy.

Today we got to look at these samples in the microprobe, and as expected from the difference in their textures noted while polishing them, they are rather different from one another. The one wherein I had issues with the welding did contain some water; we know this because there are very small grains of mica present. However, neither was it water-saturated, so it lost some due to the poor seal of the capsule. It contains many, many very tiny grains of garnet (~1 micron diameter; remember that there are 1000 microns in every millimeter) which nucleated on their own, and very thin rims of garnet on the “seeds” which had been included in the powder to encourage garnet growth. The rest of the sample is even finer grained “matrix” minerals, which are going to be difficult to analyze. The other, water saturated, sample contains fewer, larger, grains of garnet, and the rims of new garnet growth on the “seeds” are much thicker than in the first sample. While it, too, is generally fine-grained, it will be easier to find single crystals large enough to get a good analysis of their compositions (which we need if we are going to accomplish our goals).

Having had this first look at the samples we’ve set the probe to create “element maps”, pretty full-colour pictures showing which areas are high (warm colours) and which areas are low (cool colours) in specific elements. Once we have these maps, we will use them to select the grains for the detailed compositional analysis. But even before we do that, I now have a better understanding of the difference between water-saturated and water-under saturated environments in terms of the ease at which minerals grow.

Friday, 30 October 2009

Attending AGU in December

Thursday, 29 October 2009

Extending the parameters of my “1000 words a day” challenge

One of the things I’m doing here, in addition to my experiments, is taking classes in the local language. I’m dutifully doing my homework each day before it is due, but I’ve not been making much additional effort towards actually learning this language. All of my colleagues are so fluent in English that I can speak at my normal high rate of speed, so I don’t *need* to learn the language to do my job. Likewise when at the market it is easy enough to use the phrase I’ve memorized for “half kilo” and point, and then look at the numbers printed on the cash register to work out how much to pay. Again, I don’t *require* the local language to live my life here. Yet, it would be nice.

Therefore, I have expanded my “1000 words a day” to now be either read (at least) 1000 words of geologic literature in my own language, or spend 20 to 30 minutes translating something. One of my favourite books as a child was Anne of Green Gables

Wednesday, 28 October 2009

Background learning has meant a reduction in posting

Ah, writing; it is such an easy way to communicate with people—simply enter the words into a keyboard at a time of your own choosing, and your audience will have the option to read it later, at a time of their choosing. No need to arrange a face-to-face meeting with them to share your information. No need to repeat yourself over and over—one typing session can communicate to hundreds of people, should you wish it to (and, at times, even if you don’t so wish, so it is always best to be careful what you commit to the written form, lest your words be shared in a venue unexpected).

So, what science have I been doing while I was busy not writing (or, in a couple of cases, not taking the photos to accompany the writing)? So far it has been simply learning the mechanics of setting up my experiments. #1 has been run, #2 is in progress, and #3 is approaching ready to go. Next week, I am told, we will look at the results of #1 in the microprobe and see what there is to see. It will be interesting to compare the two samples. My experiments are being run with about 5% H2O and a small piece of graphite sealed into the gold capsules with the powder. When sealing the capsules it is important to do the welding with the capsule bottom surrounded by water to keep it cool so that the welding process doesn’t boil off the water before it is sealed. I failed to do this with the first capsule I filled. Likewise, I am not certain that I actually managed to get the capsule completely welded shut. If there is a small opening in the capsule it is possible for the water to boil out of the capsule early on in the experiment, and so not be available for chemical reactions.

Given the huge difference in texture between the two samples which comprised my first experiments, this may have happened for one of them. Apparently when water is present in the capsules the result is an amount of porosity in between the grains of powder, despite the high pressure of the experiment, so the end product is soft and easily torn out of the capsule after the run, if one isn’t very careful in the polishing process. However, when water isn’t present the grains of powder are pushed more closely together, and the new minerals have a chance to interlock as they grow, resulting in a much more coherent sample. One of my two samples polished up without a tendency for powder to be plucked out of it, so it is likely that this one operated under “dry” or nearly dry conditions. The other required much more care as it was soft. It was necessary to coat it with additional epoxy before the final polish to keep it from being lost. It will be interesting to compare the results of the two samples. Are there any hydrous minerals at all in the one we suspect was “dry”? I will have to wait till early next week to learn the answer to this question.

Monday, 21 September 2009

Learning to create capsules for experiments

*Step one: Prepare the holder in which the capsule will be placed while filling it

During the filling process we use small metal disks into which holes of varying diameter have been drilled as a holder for the capsules (different sized holes are needed because different experiments use different sized capsules). First find a disk which has a hole with the correct diameter (or make a new hole in a disk if necessary). It needs to be just big enough to insert the tube into, without being loose. Then use fine sandpaper to carefully polish the metal around that hole so that when you get to step 6 you will have an easier time of filling the capsule.

During the filling process we use small metal disks into which holes of varying diameter have been drilled as a holder for the capsules (different sized holes are needed because different experiments use different sized capsules). First find a disk which has a hole with the correct diameter (or make a new hole in a disk if necessary). It needs to be just big enough to insert the tube into, without being loose. Then use fine sandpaper to carefully polish the metal around that hole so that when you get to step 6 you will have an easier time of filling the capsule.

*Step two: cut the tube for the capsule

Obtain the correct diameter and metal tube (our lab uses both gold and platinum/gold alloys in a variety of sizes, I’m to use gold for mine) and then cut off a ~7 mm length from one end. To cut the tubing place it on a metal plate, then place an x-acto blade upon the tube and use the blade to exert a gentle pressure to roll the tube back and forth until the blade cuts through without squishing the tube. The back-and-forth motion is essential. This is not “sawing”, which uses a serrated blade to tear chunks out of a material which is stationary, but rather the tube itself rolls during the process as the blade slowly cuts into it.

*Step tree: Pinch closed one end of the tube

*Step four: Weld the pinched end shut

The voltage necessary for welding will change based on a variety of factors, including the diameter and length of the capsule, the thinness of the seam, the sharpness and length of the graphite in the welding tool, and what, if anything, you use to cool the capsule as you work. Unfortunately, our

welder isn't very precise and it can be difficult to adjust it to the perfect voltage for any given job. For this size we tried a variety of settings between 25 and 30 V, the 25 V was clearly too low--the welder left it looking "dirty" and coated with black, which is graphite from the welder being left on the gold. At 30 V it was too high; there is too much melting. In between that range the exact value was hard to find, and as variables change, so does the perfect voltage for the task. One variable which can make a huge difference is the sharpness of the graphite point. We have two different sharpeners, one of which makes a sharper point than the other. Using a “point” created by the duller of the two sharpeners at a voltage which isn’t high enough for that point and then switching to a point created by the sharper of the two sharpeners without turning down the voltage will result in the entire end of the tube melting.

The bit of advice I obtained the next day seems to have made a difference—don’t try to touch the gold with the graphite point, but rather hold it just barely close enough to cause an arc between them, and then try to draw that arc along the length of the seam. This isn’t easy, but I did wind up with useable results. Alas, the photo to the upper left doesn't show the welding very clearly--gold is just too darn shiny to photograph well through a microscope with a cheap camera when resting in a brass holder (this is after adjusting the brightness/contrast/intensity to make it visible at all).

I was also told that when welding I should try to start at the outer edge and draw the graphite point towards the middle, which brings excess gold from the edge towards the center to fill the small hole at the triple-junction. The goal is also to wind up with a flat bottom after welding.

*Step five: Prepare the welded tube for filling

After welding the tube it is necessary to re-shape the tube so that the capsule will have properly rounded/curving edges. We have a form (photo to the left) into which the tube is placed carefully so that the widest parts will be inside the form and not pinched between the two halves of the form (one chooses the correct diameter chamber within the form for the tube in question, of course). Once it is positions correctly the form is closed, and the tube is pressed back into a cylindrical shape. Once it has been re-shaped in the form it is put it into the holder (prepared in step one, and resting on a metal plate) and insert into the gold tube a small rod which has a diameter which just fits into the tube (in this case the rod needs to fit into a space 1.4 mm wide). Gently tap the rod with a mallet so that the bottom of the capsule flattens against the underlying metal plate and spreads out to match the curve of the sides of the hole in which the tube rests (take care as to not strike it so hard as to tear a hole in the gold tube!).

After welding the tube it is necessary to re-shape the tube so that the capsule will have properly rounded/curving edges. We have a form (photo to the left) into which the tube is placed carefully so that the widest parts will be inside the form and not pinched between the two halves of the form (one chooses the correct diameter chamber within the form for the tube in question, of course). Once it is positions correctly the form is closed, and the tube is pressed back into a cylindrical shape. Once it has been re-shaped in the form it is put it into the holder (prepared in step one, and resting on a metal plate) and insert into the gold tube a small rod which has a diameter which just fits into the tube (in this case the rod needs to fit into a space 1.4 mm wide). Gently tap the rod with a mallet so that the bottom of the capsule flattens against the underlying metal plate and spreads out to match the curve of the sides of the hole in which the tube rests (take care as to not strike it so hard as to tear a hole in the gold tube!).

After much effort I now have three small capsules with one end of each sealed and flattened, and the other end still open and ready to fill. Stay tuned for steps 6 and 7 once I get them working. Having finally managed to get the tubes ready to fill, I chose to rest on my laurels and call it good for the day.

After much effort I now have three small capsules with one end of each sealed and flattened, and the other end still open and ready to fill. Stay tuned for steps 6 and 7 once I get them working. Having finally managed to get the tubes ready to fill, I chose to rest on my laurels and call it good for the day.

Tuesday, 15 September 2009

Pre-Conference Field Trip, Stop Two: Siccar Point

This outcrop is said to be one of the most significant in the history of the study of geology. Before Hutton published his theory on geologic time many people accepted Bishop Ussher’s calculations that the earth was only 6,000 years old. However, Hutton’s observations of geologic phenomena led him to realize that it must be far, far older than that to account for the sedimentary record. He observed erosion taking place in the world around him; saw how much sand a river can carry to an ocean over time, and reasoned that this process must have been going on for as long as there have been rivers. The rate at which the sand is deposited onto beaches or into lakes, or along a riverbed is measurable, and so estimates of the time needed to deposit a given thickness of sand may be calculated. He also noted that when sand is deposited by water, it always happens in horizontal layers. Comparing such layers of fresh sand, mud, and/or gravel with layers of sandstone, mudstone, and conglomerate leads one to the realization that the sedimentary rocks must have, at one time, been made up of loose sediment, before they became compacted and/or cemented into solid stone, and any sedimentary rocks which are folded or tilted must have been tilted or folded at some point after deposition and after becoming rock (or the sand would have slid back down into flat layers again).

The rocks in southern Scotland include two very different packages. The older of these packages is made up of Silurian sediments—poorly sorted sandstones (greywackes) which have been folded intensely enough that the bedding now stands on end in many locations rather than horizontally. The younger package is the “Old Red Sandstone”, which was deposited during the Devonian. Hutton knew from his explorations in the region around Edinburgh that the red sandstones are reasonably flat-lying and outcrop to the north of the steeply tilted Silurian greywackes. He knew that there must be some place where the two rock types are in contact with one another, so he and some friends set out in a boat along the coast in search of it.

One can imagine the delight felt by his party when they discovered that contact, at Siccar Point. While it had been possible that there was a gentle transition from the steeply dipping sedimentary rock to the south into the flatter lying sandstones to the north, what they discovered was no gentle transition.

Instead they discovered evidence that the older rocks must have been deposited as typical flat-lying sands and muds of great thickness, transformed into rocks and folded so tightly that the layers now stand on end, the edges of the folds and some unknown amount of rock eroded away, and then, some time thereafter, the sands which were to become the “Old Red Sandstone” deposited atop them, before themselves becoming rock and then being subjected to erosion. Hutton argued that if sedimentary rates in the past operated on the same sort of time scales as they do today there is no way that all of that could possibly happen in so short a time as only 6,000 years. One of his companion on that trip, John Playfair, is recorded as having said that “The mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far into the abyss of time” when they contemplated just how much time the entire process would have taken.

Indeed, what they couldn’t know as they stood upon this rocky shore contemplating "deep time" was just how much time is represented by just the period of erosion between the two rock units, which has subsequently been calculated at fully 55 million years, during which an ocean basin closed and a mountain range grew.

Unlike Hutton's first boat-trip to this location, our field trip approached the point by bus, traveling south from Edinburgh, and finally stopping in a field near the coast some 55 km to the east of Edinburgh. Travellers are greeted at the stop with a first information sign at the trail head,

and a second when one reaches the point at which one descends to the seaside.

The way was steep, but, fortunately, it wasn’t a rainy day, so the grass was dry, and we made our decent safely.

We then spent a pleasant time examining the rocks, and taking photographs before climbing back up the hill to return to civilization, content in our own observations that yes, indeed, this outcrop does record simply amazing amounts of time.

Monday, 14 September 2009

A tale of two Conferences

The first conference, on Micro-Analysis, Processes, Time, was sponsored by the Mineralogical Society in the UK. Like many geological conferences, it began with a pre-conference field trip, the first stop of which I’ve already posted (and will be getting back to post about the other stops soon, now that I’m home). The conference itself had around 200 people attending (small compared to some!). The schedule was fairly typical for geology conferences, with talks running during the days (generally business hours), and people scattering to the four winds in the evenings. There were enough people presenting that Monday and Wednesday had four tracks of talks happening at once, meaning that one had to pick and choose amongst them, but, generally, things were arranged such that it is likely that if there is one talk in a session one is interested in, the others may well also appeal, meaning that I was able to simply find the appropriate room in the morning and stay put all day, rather than trying to bounce from one session to another, and risk missing the start of a talk in another room. Tuesday morning there was a single track of talks, followed by the poster session. Since my contribution for the conference was a poster, I took the time during lunch to read the other posters, so that I’d be available during the session to speak with people reading mine. I met a variety of interesting people during that afternoon session, but only had a short chat with each of them. After the conference there was a post-conference field trip (post with photos to follow). I did meet a few of my fellow field trip travelers, but the bus ride was mostly quiet or people speaking with their seat-mates, and, as it turned out, I didn’t have a seat mate.

The second conference, the Textile Forum, was quite a contrast in organizational style. This conference was set up as a setting to an experiment. The experiment was designed to quantify the changes that result in the quantity and quality of yarn spun with drop spindles with different masses and moments of inertia. Therefore the experimental part of the conference involved two one-hour sessions of spinning a day for five days in a row—each session using a different spindle whorl. As a result this conference worked on a very different schedule than the geology one. There were roughly 20 of us in attendance, from a variety of different countries.

The combination of the very different time-schedule for the conference, with the much smaller number of attendees resulted in the opportunity to get to know my fellow Medieval Textile enthusiasts much better than I did any of the geologists at the first conference. I will be happy to recognize the geologists at all next time I see them, but I now call many of the textile people friends. In short, while I found both conferences very enjoyable, with many interesting things learned, I think that I liked the format of the textile conference much better. Alas, off of the top of my head I can’t really think of a way to do a parallel sort of thing in the geosciences. What task do geologists do that would permit them to gather in a small group around a table, doing said task while conversing with one another? And what would it take to get them to do it? The spinners did their spinning (with some very oddly shaped/sized/weighted spindles “in the name of science” to see if there is a difference in how spindles behave which isn’t directly related to the spinner. But when geologists do experiments it usually involves setting something up and then going away for a period of time. This practice wouldn’t be conducive to a similar environment as was achieved in the Textile forum.

Sunday, 30 August 2009

Pre-conference field trip, stop one: Hollyrood Park, Edinburgh

Stay tuned for my next post, when the field trip moves about 40 miles south to Siccard Point, the site of Hutton’s most famous unconformity.